Reference: Six Cylinder Theory

INTRODUCTION

Work-life balance is the term used to describe the balance that an individual requires between time allocated for work and other aspects of life. This requirement references an individual’s health and wellness as it relates to stressors and stress levels. A healthy work-life balance reflects in the individual’s health specifically in three categories: physical, mental, and emotional.

The pursuit of a healthy work-life balance can be a difficult challenge. Individuals are torn between juggling heavy workloads, managing relationships and family responsibilities, and squeezing in outside interests, so it is no surprise that more than one in four Americans describe themselves as “super stressed.” And that is not balanced—or healthy.

Research validates a distressed individual or an individual unable to manage distracting thoughts and disruptive emotions will have a greater tendency for errors in judgment and demonstrate lack of memory or become more rigid and less flexible with responses.

As it pertains to work, an individual’s ability to balance the rest of life becomes critical in every aspect of human performance on and off the job.

Stressors

A stressor can be events or environments that an individual would consider demanding, challenging, or a threat to the individual’s safety. It is important to recognize that stress is a friend to human performance, distress is the enemy. Stress is the body’s way of rising to the occasion whether trivial or extreme. Distress is described as anxiety, sorrow, or pain.

In a rush to “get it all done” at the office and at home, it is easy to forget that as individual stress levels spike, productivity plummets. Unmanaged stress can harm an individual’s concentration, make them irritable or depressed, and harm relationships. Although it may be the individual’s intention to demonstrate personal best and good will, personal life and professional agendas create stressors that will often hinder human performance.

Individuals allow stress to follow them around; in the same way work stressors are sometimes brought home, home stressors can also hinder productivity while at work. Over time, an individual’s stress response system also weakens the immune system and makes an individual susceptible to a variety of ailments from colds to backaches to heart disease. Recent research shows that, left unmanaged, chronic stress can double an individual’s risk of having a heart attack.

Chronic stress is the response to emotional pressure suffered for a prolonged period of time in which an individual perceives they have little or no control. The key to this is a person’s perception of their own control—top performers learn to change their perception, thoughts, or chatter rather than focusing on external stressors from people, places, and events. A well-balanced individual will recognize when external stressors are working against one’s own ability to think clearly and respond accordingly to the moment. Top performers learn mental and emotional skills to develop self-awareness and self-regulation strategies to keep balance in the moment. When individuals are balanced, they are happy, more productive, take fewer risks and less sick days, and are more likely to be aware of their stressors and respond accordingly to maintain a healthy balanced day.

The Marketplace

The balance between work and the rest of life can be structured using a simple idea called “going to market.” Every day individuals wake up in their personal lives, leaving home and family to enter into the marketplace where individuals work and serve.

Every day mental thoughts and emotions will evolve around an individual’s six cylinders.

The marketplace is where an individual goes to work in order to serve with talent and render a financial reward called a paycheck or profits. The work and service rendered by the individual earns a profit for the individual to finance a personal lifestyle.

On any given day, an individual awakes with personal goals and objectives, enters the marketplace, works and serves, and leaves the marketplace. The balance is between the work and creating a means to provide the desired life for self and family.

Different occupations require individuals to show up in the marketplace at different times, and some require longer stays than others, but an end of work is always defined. In the United States, The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) states that any work over 40 hours in a 168-hour period (7 days) is counted as overtime since the average American work week is 40 hours—that is 8 hours per day for 5 days a week.

The FLSA creates a benchmark for every individual to consider when self-managing a healthy balance between work and life. For every 24-hour day, 8 hours of work and 16 hours of life is a starting point to consider. For every 7-day period, 40 hours of work and 128 hours of life is a starting point. This serves as a simple starting point for every individual to reference and adapt as needed based on personal goals and objectives and their own personal ability to balance work-stress and life-stress.

Humans are emotional creatures and many times “blur the lines” between personal and professional cares and concerns. Although the individual may be physically in the marketplace, the mind has the unique ability to think about many different things seemingly at the same time. Science proves an individual’s thoughts can shift between friends, family, and finance and just as quickly shift to professional people, problems, and action items.

The mind is not always present in the body, which is a leading root cause of human errors in decision-making and human performance. The mind (not to be confused with the brain) is a set of mental abilities including consciousness, imagination, perception, thinking, judgement, language, and memory. In short, referred to as “chatter.” Random chatter in the mind is as natural of a bodily function as breathing or a heartbeat.

Since the mind will drift, most often to dominant cares and concerns for the individual in that moment, mental and emotional skills are required to self-manage the work-life balance dynamics. An individual’s thought-life can now be structured to bring balance or clarity of thought using a simple theory called the Six Cylinder Theory (Model).

Six Cylinder Theory and Model

The Six Cylinder Model is a new self-checking and peer-to-peer evaluation tool. The model supports corrective actions on demand and recovery techniques for critical decision making under pressure. The Six Cylinder Model, when practiced and engaged, provides the individual with corrective actions and recovery techniques to develop personal performance and leadership influence, specifically in times of change or adversity.

The Six Cylinder Theory can be used as a simple decision-making model to help regulate distracting thoughts and emotions.

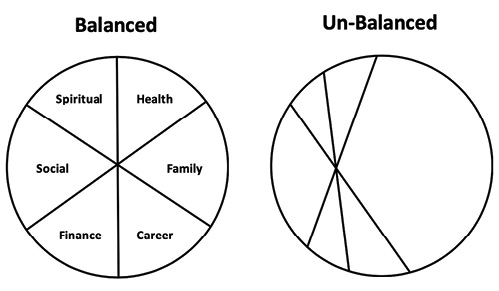

The Six Cylinder Theory engages an individual to view self in six individual cylinders. Think of how a six-cylinder engine works to support the performance of a car, with each cylinder working within its own capacity while synchronized with the others. An individual’s life operates using a very similar model; each life cylinder has its own purpose and primary role in the person’s daily life and activities. A healthy balanced mix between the six cylinders becomes the individual’s daily reference point for health, wellness, and personal best.

The Six Cylinder Model is broken down into six individual categories bringing clarity of thought for balancing work and life concerns. Each category is designed to engage the individual’s thought-process and create mental structure, specifically by prioritizing and aligning personal-life thoughts with work-related thoughts. This mental act of prioritizing directly impacts the stress response system and an individual’s emotional states.

The six cylinders and definitions are listed below in no particular order:

- Spiritual Cylinder – a relationship with a higher power, not to be confused with church, religion or ceremonial activities; an individual’s spiritual beliefs most often stem from religious beliefs, morals, and personal ethics.

- Health Cylinder – physical, mental, and emotional health. Physical health is referenced as vital signs, doctor reports, lab work, aches and pains; mental-health is referenced as attitude, habit of thought, destructive or constructive, and problem-seeking vs. solution-seeking. Emotional health is referenced as positive vs. negative emotions, disruptive vs. supportive feelings, simple awareness to all moods, and desires.

- Family Cylinder – mother and father, siblings, in-laws, spouse or significant other, children, and extended blood-related family members.

- Career Cylinder – often referred to as a job or work; talent taken to the marketplace, such as individual skills and natural abilities for work and service in return for a reward; employers and employees are found in the marketplace.

- Financial Cylinder – income and expenses. Income can be profits or paychecks and expenses are bills, bank statements, budgets, taxes, and anything associated with money.

- Social Cylinder – serenity or personal space, peace, and quiet time. This cylinder is unique to each individual allowing a mental and emotional pause from dominant thoughts; can be a physical location or mental and emotional state of being.

The Six Cylinder Theory and Model is referenced in human performance improvement as a critical decision-making model (CDM). CDMs are prevalent in the adult learning industry and most often researched and validated by our military and other high-performance organizations.

Decision-making is the process of selecting a choice or course of action from a set of alternatives. A large number of CDMs have been developed over the course of several decades. Most all of the models are designed as a mental thought process providing step-by-step engagements to examine the alternatives clearly and choose accordingly—both consciously and sub-consciously.

Whereby most CDMs follow a step-by-step assessment of external alternatives, the Six Cylinder CDM focuses the individual’s thought-processes internally, isolating specific work-related and life-related cares and concerns. When practiced daily, these CDMs improve clarity of thought and critical decision-making by developing mental and emotional skill sets.

CONCLUSION

As an individual awakes each new day, thoughts from each cylinder will randomly appear based on current and relevant concerns. Even though the individual may be physically in the marketplace working on specific tasks, the mind will randomly flash thoughts from each of the individual’s six cylinders. In the field of human performance, a randomly wandering mind is distracted and prone to errors in judgment and decision-making.

When working, the individual learns to keep the mind balanced on work tasks and activities. When the mind drifts, the individual should notice their thoughts have drifted and take the thought captive using the six cylinder framework. By placing the current thought or distraction into the proper cylinder for later review, a new thought process can engage corrective actions and recovery techniques. As often as the mind drifts off the current task, the Six Cylinder Model becomes an on-demand reference for clarity of thought and decision-making.

When practiced daily, Six Cylinder Theory improves personal performance by developing self-awareness and self-regulation skills. In advanced lessons on this topic the Six Cylinder Model and exercises develop the third competency of emotional quotient, self-motivation. Self-motivation is one of the hardest skill sets to teach in the emotional intelligence framework.

RE13140

© electrical training ALLIANCE 2019